Lecture 17

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

November 3 — Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Topics

- Review: Autoencoders

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

- GANs and VAEs: A Unified View

1. Autoencoders (Review)

Goal: Learn a compressed latent representation of input ( x ).

Structure: $ \hat{x} = f(h) = f(g(x)) $ where:

- ( $g$ ): encoder

- ( $f$ ): decoder

Variants

Denoising Autoencoders

- Add noise (e.g., dropout or Gaussian noise) to input.

- Train to reconstruct the original, uncorrupted input.

- Purpose: Learn robust representations that can remove noise.

Autoencoders with Dropout

- Dropout layers encourage redundancy in learned features.

- Improves generalization and robustness to missing inputs.

Sparse Autoencoders

-

Loss function: $ L = \lVert x - \hat{x} \rVert^2 + \lambda \sum_i |h_i| $

- Adds an L1 penalty on activations to enforce sparsity.

- Produces interpretable features — each neuron learns a distinct factor.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

- Latent variable ( $z \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)$ )

- Enables sampling new data points.

- Provides a probabilistic framework for generative modeling.

- Objective: maximize the evidence lower bound (ELBO)

2. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Overview

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were introduced by Goodfellow et al. (2014), and is a generative modeling framework between a generator that produces synthetic samples and a discriminator that tries to distinguish them from real data. Unlike autoencoders or autoregressive models, GANs can generate an entire sample with less steps.

Motivation

Traditional generative models (Gussian Mixtures, VAEs, and autoencoders) often struggle to uncover the complexity of high-dimensional data like that of images. GANs are flexible and capable of learning implicit data distributions. This makes them useful for image synthesis, style transfer, and text to image applications like those developed by OpenAI (DALL-E 2) and Google (Imagen).

Architecture and Training

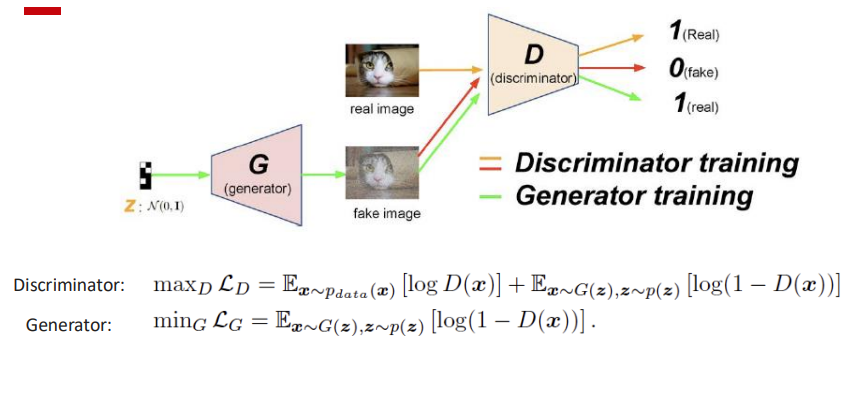

Generator ($G_\theta$)

- Maps a noise vector $z \sim p(z)$ (often Normal(0, I)) to a data-space sample $x = G_\theta(z)$.

- Goal: produce samples indistinguishable from real data $x \sim p_{data}$.

- Fool the discriminator (increase $D(G(z))$)

- Trained via gradient descent to minimize $-\log D(G(z))$.

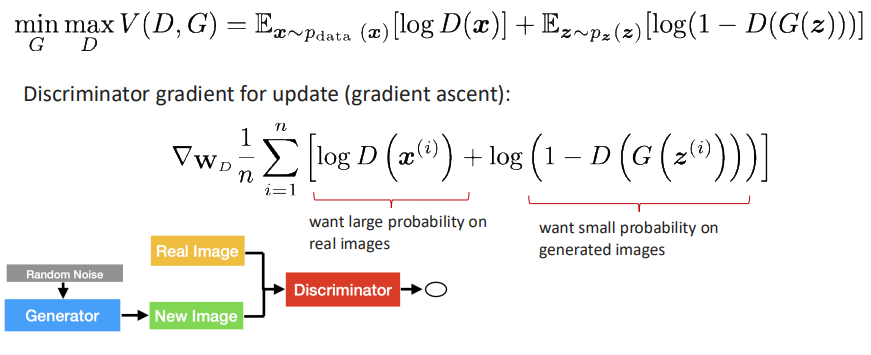

Discriminator ($D_\phi$)

- Binary classifier outputting $D_\phi(x)\in(0,1)$, interpreted as $P(\text{real}\mid x)$.

- Trained to assign high probability to real data and low probability to generated data.

- Discriminator loss (binary cross-entropy form):

- Updated by gradient descent on $\mathcal{L}_D$.

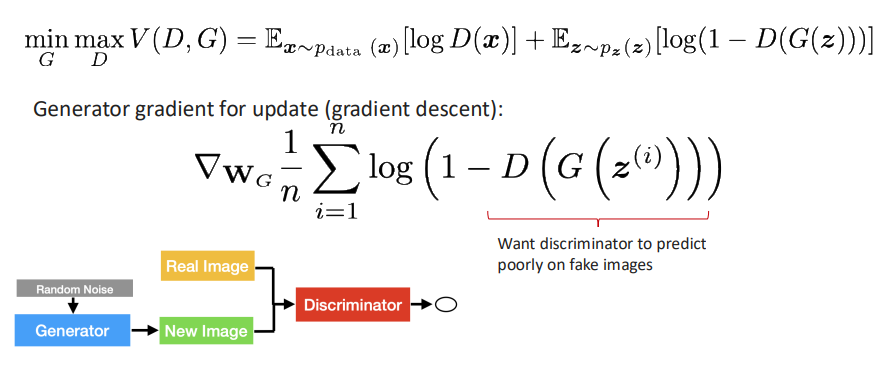

Minimax Objective

“max” and “min” Objective

The discriminator outputs a probability $D_\phi(x)\in(0,1)$ interpreted as $P(\text{real}\mid x)$. The GAN game is:

\[\min_\theta \max_\phi \; \mathbb{E}_{x\sim p_{\text{data}}}[\log D_\phi(x)] + \mathbb{E}_{z\sim p(z)}[\log(1-D_\phi(G_\theta(z)))]\]- Discriminator step ($\max_\phi$): increase $\log D_\phi(x)$ for real $x$ and increase $\log(1-D_\phi(G_\theta(z)))$ for fake samples. This pushes $D(x)\to 1$ and $D(G(z))\to 0$.

- Generator step ($\min_\theta$): make generated samples look real, i.e., push $D(G(z))$ upward (toward 1). In practice, we use the non-saturating generator loss for stronger gradients:

The generator minimizes this value by making its outputs hard to distinguish, while the discriminator maximizes it by improving classification.

Training Characteristics

Training alternates between both networks. Convergence ideally occurs at Nash Equilibrium, where the generator’s distribution equals the true data distribution and the discriminator outputs 0.5 for all inputs.

In practice training is often unstable:

- Oscillatory losses between G and D

- Mode collapse (one prototype sample repeated)

- Vanishing gradients if D dominates this can lead to non-saturating loss being recommended

- Hyperparameter sensitivity (learning rate, architecture, batch size)

- If the discriminator is too strong, gradients for $G$ vanish and training stalls.

- If the discriminator is too weak, $G$ can exploit $D$ and generate unrealistic samples that still fool it.

Interpretations and Variants

A pure equilibrium may not exist, which explains observed oscillations and non-convergence.

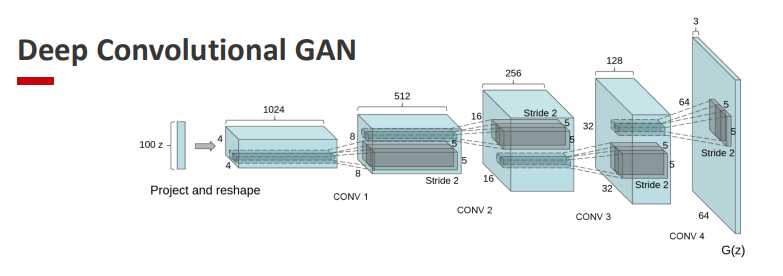

Deep Convolutional GAN (DC-GAN)

Introduces convolutional architectures to stabilize training and capture spatial features.

3. GANs and VAEs: A Unified View

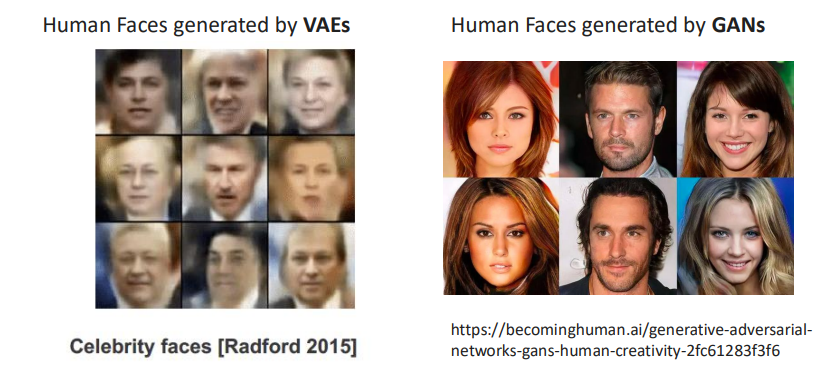

GAN is minimizing the KL divergence between $P_{\theta}$ and $Q$. On the other hand, the VAE is minimizing the KL divergence between $Q$ and $P_{\theta}$. GANs tend to miss the mode, whereas VAEs tend to cover regions with small values of $p_{data}$.

A Unified View

| Feature | Autoencoders (AEs) | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | GANs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal | Learn latent representations | Probabilistic generative model | Adversarial generative model |

| Latent Variable | Deterministic ( $h = g(x)$ ) | ( $z \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)$ ) | ( $z \sim p_z(z)$ ) |

| Training | Reconstruction loss | ELBO (KL + reconstruction) | Adversarial minimax loss |

| Sampling | Deterministic decode | Random sampling via latent prior | Generator sampling ( G(z) ) |

| Weakness | Not generative | Blurry outputs | Instability in training |

VAEs vs. GANs: a cloesup

| Aspect | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Single ELBO maximization | Two opposing objectives ($\min_G$, $\max_D$) |

| Regularization | KL term via prior $p(z)$ | Implicit regularization via adversarial feedback |

| Inference Model | $q_\phi(z \mid x)$ | $p_\theta(x \mid y)$, $q_\phi(y \mid x)$ |

| Generation | Explicit probability model | Implicit distribution (no likelihood) |

GANs can be expressed in a variational-EM-like framework:

- E-step: update discriminator to approximate $q_\phi(y \mid x)$

- M-step: update generator to improve $p_\theta(x \mid y)$

Common Problems

| Problem | Explanation | Typical Fixes |

|---|---|---|

| Mode Collapse | Generator outputs few modes of data | Mini-batch discrimination, WGAN, feature matching |

| Vanishing Gradient | Discriminator too strong | Non-saturating loss (maximize $\log D(G(z))$) |

| Training Oscillation | No stable equilibrium | Gradient penalty, slow updates, learning-rate tuning |

| Over-fit Discriminator | Memorizes training data | Dropout, label smoothing |

Empirically, GANs generalize only when the discriminator capacity and training data are balanced.

Otherwise, Jensen–Shannon and Wasserstein divergence analyses can be misleading in finite settings.

References

- Goodfellow et al. (2014) Generative Adversarial Nets (NIPS).

- Arora & Hardt (2017) Generative Adversarial Networks: Some Open Questions (OffConvex Blog).

- Radford et al. (2015) Unsupervised Representation Learning with Deep Convolutional GANs.

- Hu et al. (2017) Unifying Deep Generative Models.